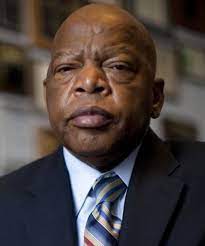

In his work as a civil rights activist and then as a US Representative, John Lewis was known for causing what he called “good trouble.” Lewis died at age 80 in 2020. From a CNN review of the movie about the civil rights movement by Dawn Porter…

Lewis’ approach to politics is guided by his belief in good, necessary trouble – that is, by a willingness to confront the world’s many injustices, regardless of the consequences. (Lewis recalls that he was arrested 40 times in the 1960s and has been arrested another five times since he’s been in Congress.)

“I tell friends and family, colleagues and especially young people that when you see something that’s not right or fair, you have to do something, you have to speak up, you have to get in the way,” as Lewis put it in 2018.

In my work as the Founder and Executive Director of the Center for Creative Conflict Resolution, I have always intended to cause good trouble. This has struck many as odd because it seemed that I was causing conflict while saying I wanted to resolve conflict. This confusion arises out of failure to differentiate between the cause and the expression.

A system may appear calm because there are constraints that keep latent tensions from coming to the fore. When those tensions are pointed out… brought to the light… they are suddenly visible. It appears that the conflict was created when in fact it was now revealed. It now has expression.

Unexpressed conflict is real and is harmful. Conflicts cannot be resolved unless they are addressed, and conflicts cannot be addressed unless they are first named. The first step in helping systems work better is to name the dynamics that impair healthy functioning. However, if you point out the ways that systems are unjust, you are seen as starting a conflict.

The arena in which I have expressed my ministry has changed. In the early years of the Center for Creative Conflict Resolution the primary focus was on interpersonal violence and the violence within the perpetrators that was expressed towards those the offender claimed to love the most. I largely worked with men who batter and sexually abuse.

But out of that work I came to see more and more how the way we behave as individuals is inspired by and expressed in the larger systems of which we are a part. I saw that the process of the domestic violence intervention community was itself an expression of the very abuse we were trying to address.

I urged my colleagues in the DV community to engage in critical self-reflection. I suggested that we discuss what we envision as healthy relationships between women and men and with that, what we would hope would be the relationship between programs that work with women and those that work with men. I was met by ad hominem attacks and counterfactual claims about my work. I suspended the Abuse Prevention Program and started working on conflicts in other complex adaptive systems.

Ambivalence about critical self-reflection

In 1993, when Joan and I joined Pilgrim, among the members were Gerald and Ida Early. Gerald, a professor at Washington University and a prominent essayist, was acting as the editor of a quarterly journal of writings by members of the congregation.

In an edition of the journal shortly before we joined, the cover article was one that he himself had written about what he saw as the need for Pilgrim to have a conversation about race. He applauded the comfort with which Blacks and Whites and Asians could worship together, but he urged Pilgrims to be self-reflective about how we each understand the nature of race and how it shapes how we interact with each other.

The Earlys left Pilgrim a few years later. I don’t know if they gave a reason for moving their membership, but the conversations that Gerald had called for had not happened.

In the mid-90’s Barney Kitchen got two requests to officiate at commitment ceremonies for gay couples. Rather than address these requests quietly, he threw the matter open to the Congregation by hosting conversations as an Adult Education class and with the Woman’s Association. In the end Fred Eppenberger settled the matter in the manner of a clever lawyer. The Council, following his direction, moved that, when members of the Congregation approach the Minister for pastoral care, it is not for the Congregation to determine how that care will be offered.

Barney did the services. He always wanted to. He could have demurred saying that people would object. He could have done them quietly. But he invited a conversation about the issues raised. Rev. Kitchen saw the conflict and he leaned into it, he grabbed it and pulled it up into the light.

For many years Pilgrim had a Reconciliation: Next Steps Initiative that functioned to produce conversations at Pilgrim. One was about members’ reaction to the red or the black hymnal, and another led to Pilgrim proclaiming itself to be Open and Affirming. [It is sad to note that Pilgrim had more gay persons and couples in its membership before that conversation than at any time since.] The Initiative had as its core purpose to construct conversations about issues on which the Congregation was divided.

In the Spring of 2014 Pilgrim sponsored an Encounter which invited the larger community into a conversation about multi-racial families. Some of these families were the result of marriage but most were from adoption. The event was sufficiently successful that a second Encounter was discussed but not manifest because of the resignation of Allen Grothe.

In the last days of Rev. Grothe’s pastorate, Pilgrim was offered a grant to help pay for its participation in a program by the Hope Initiative, a project affiliated with the Disciples of Christ, which was called New Beginnings. Pilgrim embraced the program but unfortunately it did not begin until nine months after Allen left. By then the interim pastor was Felicia Scott. She complained that she hadn’t been told about the program, and she was not a fan of it.

The first two phases went well. First was an information gathering portion conducted by an employee of the Hope Initiative, and second, a series of meetings in small groups in the homes of members. In the absence of pastoral leadership, some of the women who had offered leadership to the home groups continued the process to a report, very cleverly expressed as a play about what Pilgrim might look like five years hence. That play was presented to the Congregation in the Sanctuary in the Fall of 2016. By then the Council had fired Ms. Scott and Chance Beeler was serving as the Interim.

The New Beginnings process was intended to result in a bold decision. This was so central to the concept of the program that it was always written as BOLD. I assumed it was an acronym for something, but, no, it was just a clear affirmation that the process would lead to one of three conclusions. These were either that the congregation will decide that everything is fine, and they will continue to do what they have done; or that the future is such that they will have to do new things, actions that are specifically defined; or that the future for them is so bleak that they will find another ministry to which they will gift their assets.

The central positive result of the process at Pilgrim was to affirm that we will have to offer the building for the use of other organizations. We must both generate the income we need and make the resources of the building available to “incubate” services to the community. There were no specific actions that the Congregation itself was to make. To my understanding of the process, it was not yet complete.

Chance resigned after a few months and Pilgrim hired Colleta Eichenberger to be the Interim “for a few months.” She was with us for a year and a half.

In the summer of 2018, Pilgrim contracted with the Walker Leadership Institute at Eden to lead a retreat at the Mercy Center. The report they promised us was never delivered, but our recollection of the conclusions informed the profile that led to the call of Rev. James Ross. The Call was to be a Designated Term Pastor for a term of three years with the designated purpose being to lead Pilgrim through a process of discernment about its future.

At this point I was myself serving on the Committee on Ministry. I was recused from any actions that bore upon Pilgrim so I don’t know details, but the fact that this was the first time the CoM had authorized a call for a designated term position could not be missed. The purpose of this placement was the discernment of the future of Pilgrim. Rev. Ross started in December 2018. In May of 2019 he hosted a conversation held at Union Ave about a strategic plan for Pilgrim.

Rev. Ross and I agreed that the appropriate role for me was to enter into a Four-Way Covenant between the Council, the CoM, myself, and the Board of the Center for Creative Conflict Resolution. [This was like the one we created when Cindy was Pilgrim’s pastor but without reference to work in the DV community.] The Pilgrim Council approved the covenant in August of 2019.

Rev. Ross announced his resignation in November of 2020 and left at the end of January 2021. Other than the notes he compiled after the May 2019 meeting, he left no document presenting a plan or his thoughts about Pilgrim’s future.

My ministry to the “future church”

I was ordained in January of 1977 at a service at Calvary UCC in Overland. The basis of that ordination was a call to the St. Louis Young Adult Ministry. It was supported by the national church and the President of the UCC spoke at the ceremony.

The ministry struggled along for a couple of years and finally failed because of a central oversight on the part of myself and my advisors. It was that, while the concern to engage young adults in a faith community that worked for them was something that all the congregations and even ecumenical partners strongly favored, their support did not include encouraging the young adults from the families in their congregations to participate. Even though these young adults were no longer active in the life of their congregations, the leadership of those churches did not want them to be active elsewhere. They were in effect saying, “We love what you are doing. Just don’t include our kids.”

Though that work is long past, that concern has always flavored my pastoral concerns. While my experience of the church has been a powerful and positive influence on me, and thus something I want to preserve, the reality is that, without the participation and leadership of young adults, local congregations will wither and die.

In the last quarter century these social concerns have been informed by my love of science broadly and particularly by the science of complexity. Observations in this field inform how we understand the vitality of complex adaptive systems like marriages, families, and local congregations.

While I have written a lot about this elsewhere, I will simply summarize it here by saying that we can confidently observe that local congregations are in decline everywhere and that this decline is not a result of the recent failures of the congregation. This decline is not because the congregation can no longer do what it used to do. It is that ‘what the congregation has always done’ is no longer doing ‘what the world around it needs.’

No matter how well a local congregation does what it had always done, it will fail bit by bit if it does not adapt to the needs of the larger community. But if what it is doing is consistent with its perception of its own purpose, and it addresses the unmet needs of the larger community, it will thrive. This is true for all complex adaptive systems.

The key to the necessary transformation is a willingness to engage in critical self-reflection. There is no structural reason why local congregations can’t do the necessary work of transforming into communities that thrive. The barriers are cultural. I remember hearing many years ago the quip that the last words of the church are, “but we never did it that way before.”

Offering my ministry for the future of Pilgrim

So, when in January of 2021 Rev. Ross left his designated term position without having completed the mission, I was both alarmed and excited about the possibility of doing something creative that would restore Pilgrim’s vitality and make it a model for the rest of the denomination and for the world. I foresaw a process of critical self-reflection that could help Pilgrim discover what it is called to be which the larger community most needs.

I brought my vision to the Council, and I got their permission to craft a process that I called New Beginnings Redux. At every point in that process, I shared what I was doing and never acted without both the awareness and the approval of the Council. I have detailed the process elsewhere, but the high points are that the people who volunteered to help by becoming the Discernment Team were awesome. There were twelve people who were broadly representative of all aspects of the Pilgrim community. They were diverse in age, gender, race and their roles in the community. And they bravely tackled the work before us.

I want to be clear that my role was to create the container but not the contents. Every decision was by consent and every report I wrote was considered by and consented to by the whole team. The work of the Discernment Team is better than anything I could have done by myself.

The work was done during the summer of 2021 and reported to the Congregation that fall. Some follow-up work was done in the Spring of 2022 and the final report made to the Congregation at the Annual Meeting in June of 2022.

While I think there is some fascinating detail in the final report, the summary is simple. The Discernment Team believed Pilgrim can find greater vitality and meet the needs of the world if it critically reflects on four things; what is Pilgrim’s purpose, how can it best communicate with itself and the world, how it can improve its governance structure, and how it can be a better steward of its resources including its members, its staff, and the building and investments.

It has now been over two years since these recommendations were offered to the Congregation and the Council. None of them has been considered by the Council and recently, at the June 2024 meeting of the Council, when members of the Council raised matters relating to the recommendations, the Pastor, Rev. Anthony, waived them aside saying we wouldn’t be looking at them. They are not considered to be consistent with what Pilgrim needs to address now.

My changing relationship to Pilgrim

All of this is a prologue. This allows me to put into context what happened on August 29, 2024, when I was invited to meet with Rev. Kevin Anthony. Pastor; Hardy Ware, Moderator; Jeff Webb, Vice Moderator; and John Gandy, who is a member of the Committee on Ministry of the St. Louis Association. I got 23 hours’ notice of the meeting, but I had been anticipating it for a bit over seven months.

When Kevin accepted the offer to be Pilgrim’s pastor in December 2023, I was pleased. I had come to know him first as someone who regularly participated in a conversation I hosted with clergy about the current state of local congregations. We called it We Should Talk about the Future of the Church. These conversations were all by Zoom.

From those conversations I knew something about his circumstances, and I got his permission to give Connie Agard his contact information when she chaired the Search Committee for a bridge pastor. He was subsequently employed as Bridge Pastor from June 2021 to June 2022.

I was surprised that the Search Committee for the called position didn’t call him but instead chose Merrimon Boyd. Pilgrim determined that it could not afford a full-time pastor. When Pilgrim decided to create a part-time position, I encouraged Kevin to take it. He was reluctant because he wanted a full-time gig. I told him that I thought Pilgrim needed him. I was pleased when he decided to take it.

It seems I am the go-to guy for electronic equipment and I took it upon myself to find out what he needed and to shop and deliver and set up the computer, monitor, and printer. Amid all that, I let him know that I wanted to have a conversation with him about what he wanted my role to be in relation to him and to Pilgrim.

Since the first Four-Way Covenant when Cindy Bumb was pastor, I have had essentially the same conversation with every called pastor. As I am an authorized minister in the UCC, I have restrictions on how I can relate to a local congregation. We pretty much ignored those restrictions for the first decade I was a member, but after the debacle that was the Tom Bentz Interim, I have been very careful.

With Allen Grothe I was an associate. During certain other periods, especially when I was an interim or sabbatical pastor elsewhere, I was just gone. But mostly we have had a Four-Way Covenant. I just needed to know what Kevin thinks will work best for him and for Pilgrim. This is not a negotiation. He has all the power. Whatever he says is what I do.

So, on January 23, 2024, when his new computer equipment was all installed and ready to go, I reminded him of the conversation I wanted to have about my role. It seemed to me that he remembered that I had mentioned this earlier, but he wasn’t ready to have the conversation at that point. I suggested we find a time. He pondered that and suggested Tuesday, April 9. I didn’t want to wait that long, but he seemed to want to push the conversation back to after Lent.

On April 7, a Sunday, I mentioned to him after worship that I would see him on Tuesday. He looked puzzled for a moment, and then said he couldn’t do that as he would be in Jeff City that day. I asked when we could meet, and he said he would email me.

By now I was clear that he was not eager to have this conversation, so I wasn’t surprised when he didn’t get back to me that week or to speak to me the following Sunday, but I was totally unprepared for the sermon he gave on April 21.

He started the sermon by asking how many of us, by show of hands, had ever been in an organization in which there was someone who was a troublemaker… someone who just seemed determined to cause problems. He went on to share the history of how Rev. Monteith, after being the organizing pastor for Pilgrim, was courageous enough to leave when it was clear that most of the congregation wanted to go in a different direction than he.

I had no doubt that he was talking about me. It was clear that he wanted me gone, and the following week I told the Nominating Committee that I would not be continuing to serve as Treasurer.

On May 5, the day of his installation, In the lull between the morning service and the installation itself, I approached him in the parlor, in a public space but not within the hearing of others, and said to him, “It is my understanding that your position is that it is in the best interests of Pilgrim that I minimize my leadership. Is that correct?” He waved his hand, said we would have to talk about that later, and walked away.

In June and July, I communicated to him in writing both on paper and by email. He never responded to any of my letters. Joan put a note in the prayer box encouraging him to contact me. He didn’t respond to her.

And then, in mid-August, while he was on a private Zoom call with her, she again brought up her wish that he would talk to me. He responded that he was not yet ready to do that.

While this was a small thing, it seemed huge to me. He was for the first time acknowledging that we have a pending conversation that he is putting off.

Then on Monday, August 26, as the Pilgrim Council was meeting by Zoom, I found my wife, Joan, in the kitchen. She is the Secretary of the Council. “Is the meeting over already?” I asked. She explained that she was asked to leave the meeting while the Council discussed an item in the agenda which was simply “Four-Way Covenant.”

I hope that previous pages will have put this event into context but just to be fully clear,

- I am the only person who has had such a covenant with Pilgrim in 30 years. There was no way this was about anyone else but me.

- I had what I understood to be an existing covenant, which is now five years old, and which was fashioned with the Council when Rev. James Ross was pastor. I didn’t ask that we create a new one, and I made it clear that, were it Kevin’s wish that the existing one be revoked that was entirely up to him.

- Normally when the Secretary is not in the room for a meeting, someone takes the minutes. I suspected that no one had done that. [I mentioned this to the Vice Moderator, and he confirmed that no one had been charged with keeping the minutes. He may generate something, but, as of this writing, no one has come forward to give the standard information that would normally be in the minutes.]

On Wednesday afternoon [8/28/2024] at 2:00 I got an email from Kevin inviting me to a meeting on Thursday at 1:00. I would normally need more notice than that, but fortunately I was available. I let him know that I would be there.

The invitation said the meeting would be between himself and three others. I had earlier thought of inviting him to have others present when we met so that he would be more comfortable. I was pleased that he had done so.

I purposely chose to sit next to Kevin. I didn’t want to be opposite him. We chatted about the play that would be presented in the sanctuary over the weekend. John Gandy representing the Association was the last to arrive.

I am pretty sure I could give a verbatim of the conversation. It took less than half an hour. Here are the highlights.

The purpose of the meeting was to present me with a letter to inform me that the Pilgrim Council will not be entering into a Four-Way Covenant with me.

This was quite puzzling to me. I had not asked to have a covenant crafted. In fact, I was waiting for Kevin to say whether he thought that would be appropriate. I thought I had made it very clear that it was his call and that I would consent to whatever he thought best. We were now making a big deal out of an item that could have been settled by his having told me seven months ago that he didn’t want that.

When I asked about the existing covenant that had been created in August of 2019, I was told that, because no one from the Committee on Ministry has signed the document, it was considered to have never been. This is preposterous. If the CoM were to decide to invalidate the previous agreement, I would have been told. CoM wants authorized ministers who are not serving local congregations to have such covenants.

As for the letter, it was not presented to me until the meeting ended. At multiple times in the meeting, I was told that the question I was asking was made clear in the letter that I was there to receive, but which had not been presented to me. As the meeting was ending, I asked to see the letter, at which point Kevin went to the copy machine and made me a copy. Then he closed the meeting with prayer. I didn’t get a chance to read the letter until I was in my car.

The letter has three paragraphs. The first paragraph says thank you for writing a letter about your relationship with Pilgrim. The second paragraph says that, after consulting with the Conference and the Association and the Committee on Ministry, the Council has decided that Pilgrim won’t be continuing a Four-Way Covenant. The third paragraph says, don’t let the door hit you on the way out. It assumes that I will be transferring my membership.

When, in the meeting I asked about whether I was being asked to move my membership, Kevin vigorously insisted that my membership was not at issue and that the topic had never come up.

Kevin was very concerned that the conversation we were about to have might be contentious and worried that it might cause discord and division in the congregation.

Again, I found this puzzling. I cannot imagine what the discord would be. The only discord of which I was aware of was by me towards him for ghosting me for seven months. The only people who knew anything about this from me were my wife and the Nominating Committee when I explained why I was not going to continue to serve as the Treasurer.

But Kevin was quite agitated about this, and it was clear that he was afraid that I was going to make trouble.

I was eager to clarify how the Congregation would be informed in a manner that would not cause strife.

I asked twice that we get clear about what the messaging would be to the Congregation. I wanted to know what I could acknowledge that would not be seen as causing strife.

The second time I asked this, in the dance around the fact that there was no clear messaging coming forward, John Gandy pointed out that the only way there would be any strife was if I told someone what happened. Otherwise, no one would know.

I decided not to respond to this. For one thing, if the Council has considered and acted on this, then fully a quarter of the Congregation already knows. For another, this says that if there is any controversy it is my fault for telling people what is going on with me. I should just put up and shut up.

I wanted to know what motivated the decision to deny and delete a covenant.

This was particularly frustrating for me. If my behavior has been so egregious as to require this response, it seems that someone would be able to describe the problem to me. I resorted to suggesting things that might be at the heart of the matter but none of the things I raised were affirmed as the cause. At one point I asked if this was about the New Beginnings Redux process. Jeff agreed that it was, but then Kevin quickly said that was not the case.

What I heard was that I am a troublemaker who is trying to take the church in another direction than it wants to go. Since I had acknowledged knowing that people found me troublesome, I should know what it was that I was doing that was the problem. My sense is that what this is about is that Kevin feels unsafe with me, but I have only tried to be his ally. I can’t understand why he would fear me. I will explore this below.

I was asked why, if having a Four-Way Covenant was not something I wanted to fight for, would I be upset about this action.

The loss of the covenant is very painful, but it pales to the pain inflicted by people I have reason to expect will treat me with care and concern.

Kevin has been unwilling to acknowledge my request for clarification about what he wants for my relationship with Pilgrim. His avoidance has kept me sitting on my hands and feeling not only disregarded but disrespected. In the meeting he responded to a letter I sent him at the end of June. He was the only recipient of that letter. In it I let him know that the discord I was feeling with him had resulted in symptoms that I consulted my internist about. We concluded they were emotionally induced. Kevin never acknowledged that impact and thus offered no remorse.

Instead, I get a meeting with representatives of various bodies who have been talking about me and my circumstances at what appeared to be some length. Everyone is in the loop except for me.

What makes me a troublemaker

I want now to return to the question of what I might be doing that is the source of this trouble. I have a great reluctance to name what I think is going on with others, especially others who are unwilling or unable to tell me themselves. For this reason, I want to assure anyone who reads this that I am happy to be wrong about any of this.

This situation seems to me to be quite complex. There are multiple causes and they each reinforce each other. If only one of two were present this might not have the energy that it seems to have now. The intersecting issues have to do with matters of authority, innovation, and critical self-reflection.

The complexity of these issues makes it hard to know where to start. Because the central theme is that I am causing trouble, let’s begin with what I am saying that some find troublesome. I am making three assertions about the church.

- The institution of the local congregation, once so central to American life for towns and families, is now in decline. This is not because existing institutions are not doing well what they are doing, but that what they have historically done no longer addresses the needs of a rapidly changing culture.

- When we assess the criticisms of the church broadly, and we look at what the current culture needs by its own assessment, and consider which of those cultural needs are things that local congregations could address, we can see that there are ways of being the church that are open to local congregations, and we can confidently assume that, should local congregations seek to meet those needs, they will thrive.

- These ways of being a local congregation are not things that are structurally contrary to what has been, but they are sufficiently discontinuous culturally with the old ways of being to be a real stretch. They require more than what existing congregations believe they can do and that they are willing to do given that they are mostly populated by older folks.

This is broadly about all local congregations, but as I am a member of Pilgrim, it becomes focused there. Regarding those matters about which Pilgrim is unique, those qualities make Pilgrim poised to be both very successful and a model for other congregations. Pilgrim is situated geographically, sociologically, theologically, and historically in a powerful place that no other congregation holds. The promise is immense.

And I certainly understand that my holding and espousing this set of beliefs is troubling, and that it means that I am trying to take Pilgrim in a different direction.

To the charge that I have a vision for Pilgrim that is both different and challenging, I plead guilty. But if that were the only issue, I could be dismissed as a crank. I am also an organizer.

When the New Beginnings process failed to complete its mission [through no fault of Pilgrim I must add], and when the Designated Term Pastorate of James Ross ended prematurely; I saw the promise that is Pilgrim slipping away. I badgered the Council into allowing me to conduct what became the New Beginnings Redux process.

That process was great! It was a great group of people who were highly motivated and hardworking, and we created a sound set of recommendations. There was just one problem. The convenor was not the pastor. The process may have been seen as illegitimate because my only authority to administrate the program was a contract between the Council and Center for Creative Conflict Resolution. And even though we did all of this with clarity and transparency, it is also true that I am a member of the Congregation, and I am not the Pastor. Even though the Discernment Team included both Council members and staff, including the Pastor, it was not led by the Pastor.

Thus, I am troublesome because I am urging unwanted innovation, and I am subverting pastoral authority. But there is another issue, one central to the mission of the Center for Creative Conflict Resolution. I am urging that we engage in critical self-reflection.

When I was hosting the conversations we called We Should Talk about the Future of the Church, I was eager to include Ginny Brown Daniel, the Conference Minster, in the process. While she was sent all the emails, she never entered the Zoom room. At one point when we were going to expand the conversation, I made an appointment to speak with her in her office.

She acknowledged the email and knew what we were doing, but was very clear that she thought encouraging congregations to engage in the sort of critical self-reflection we were constructing was dangerous.

We agreed that if congregations were to conduct such conversations they would discover and express latent conflict that was impairing the function of the community. And we shared the concern that the pastors of those churches might not be well equipped to address and resolve those conflicts. But we clearly disagreed about how the Conference and the Associations should respond. I thought we should offer those pastors training and support. She thought we should let sleeping dogs lie.

This is a huge issue. Central to the philosophy of the Center for Creative Conflict Resolution is the belief that all conflicts can be resolved, and that to do so is a creative act. To resolve a conflict, it must be addressed. To address a conflict, it must be named. And when conflict is resolved, the result is the transformation of the system in which the conflict arises such that the system is more vital and resilient.

Bottom-line: if systems like local congregations are to survive the current changes in human culture they will have to engage in critical self-reflection. It is the failure to do so that is dooming our churches.

I am a troublemaker. I believe in distributed decision-making. I do not think the way humanity favors dominance hierarchies is in line with the ways that God creates. It is certainly not in harmony with the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. We must examine how we understand the nature of and uses of authority.

I am a troublemaker. I have a vision for the future of the local congregation that is vital, but which requires us to move outside our comfort with the present and into engagement with the future. There are non-essential ways of being we will have to abandon. There are healthier practices we can adopt.

I am a troublemaker. I side with the science of complex adaptive systems which vividly demonstrates that systems that fail to be open to new ways of being… ways of being that are revealed to them by processes of critical self-reflection… will be overcome by entropy and will become rigid and exhausted. Organisms that cannot regulate themselves will die.